Gamification Strategies for Massage Classrooms

Gamified learning uses gaming elements and game-design principles in nongame contexts to engage and motivate students. Today, you can find gaming elements in K12 and higher education classrooms, online courses at all grade levels, corporate training programs, conferences and workshops, self-directed learning apps, fitness programs, consumer loyalty programs, and more.

Many of the learning management systems (LMS) schools use to organize their content or offer online classes incorporate gaming elements. Additionally, programs like Confetti, Kahoot, or H5p allow teachers to create games students can access online. However, even in brick-and-mortar classrooms, we can utilize games and gaming elements to make learning more fun.

In this article, we’ll discuss the benefits and challenges of gamified learning, the principles and components of gamification, and example activities, emphasizing teacher-created content for brick-and-mortar classrooms.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Gamified Learning

When used appropriately, games and gamified learning can enhance adult comprehension and recall while making content more interactive and rewarding. At the beginning of classes, games make great warm-up activities that prepare learners by enlivening previously learned content. Games anchor newly learned concepts at the end of classes and require students to apply their knowledge. Games give students a break from intense work in the middle of classes or help teachers raise their energy if everyone has lapsed into a post-lunch lull.

Most students find the reward systems common in gamified content motivating. Rewards can sharpen student focus and help them push through difficult or dry material. Similarly, immediate feedback through carefully planned gaming elements supports students as they fine-tune their understanding of concepts or practice skills. Games are memorable, so they increase effective recall. Gamification also influences student behavior, encouraging better study habits and active learning.

On the other hand, we must plan carefully to avoid some of the challenges of games and gamified learning. First, games or gaming elements must have a clear educational purpose and not distract from learning objectives. Therefore, teachers must take the time to carefully develop games based on accurate, practical, and well-structured content. In addition, games can’t be so complex that they cause confusion or require lengthy explanations that eat up class time.

Some adult students view games as a waste of time and gamification elements as a means to over-complicate the grading system. We can win these students to “gaming” with thoughtful activities that reinforce the concepts that show up on quizzes and exams. If games improve student knowledge and performance, students will view them as an engaging plus, not a distraction.

Gamified learning tends to be competitive, leading to a stressful learning environment where even the winners feel a heightened sense of anxiety. Teachers reduce the competitive element in games by using team activities or having students compete only against themselves.

Finally, games or gaming elements must be accessible to all learners, considering different abilities, time commitments, and access to resources. For example, games often use timed activities to increase rigor and challenge. For students with naturally speedy cognitive processing ability, the timed aspect of games enhances their learning experience – the game is more fun. For students with slower processing speeds, the game can feel like it’s over before they even get started. Playing games in rounds where the first round is slow and the last round is fast can make a game more accessible to all students.

Principles of Gamified Learning

Gamified learning principles adapt the mechanics that make games engaging and motivating to educational contexts. Features like earning points, unlocking new levels, comparing progress with others, competitive quizzes, challenges, prizes, rewards, collaboration tasks, contests, and leaderboards can bring an element of playfulness (and competitiveness) to learning. Let’s examine the core principles and components of gaming and how they relate to learning in massage classrooms.

Levels, Challenge, and Mastery

Games typically have levels. When you master the content in the first level, you progress to the second level, and so forth. Each level represents increasing difficulty. When you’ve achieved the final level, you’re a “master.”

Striving for mastery and the increasing rigor of more challenging content keeps learners in an ideal “game state” where they feel engaged and driven to achieve the next level.

For example, imagine a muscle game where the first level is locating and palpating the edges of easy-to-access muscles. The muscles in the second level are more difficult to palpate, and the third level is harder still. You don’t get to move up a level until you can accurately palpate – on demand – all the muscles in your current level.

Progress Tracking

Automated progress bars or completion percentages show players how far they’ve come in online learning. In brick-and-mortar classrooms, posters or status boards serve the same purpose. For example, in the muscle game, we just discussed, we might print an image of each muscle in the game and post it on the back wall of the classroom in the order it appears in the game. As students demonstrate they can palpate particular muscles, a star with their name on it moves forward. Everyone can see where they’re at in the muscle challenge and who is leading the game.

Instant Feedback

When we play games and get things right, we get a little surge of dopamine and a feeling of satisfaction and pleasure – one of the reasons games are addictive. Games provide instant feedback on knowledge demonstration or task completion to keep players chasing the dopamine hits. Admittedly, providing instant feedback during classroom activities isn’t always possible. However, as we plan gamified learning, we can think about how to give ongoing feedback to keep our students motivated.

Competition

Games are competitive, with winners and losers. When we gamify classroom content, some learners engage more regularly and deeply with educational materials to outperform their peers. Competitive games have clear objectives that help learners focus their efforts. A desire to win can push learners to improve their skills and knowledge.

However, not all learners are motivated by competition, and for some, falling behind can feel humiliating. Even for the leaders, the competitive aspect of gamified content can lead to anxiety, which may cause dishonest behavior and cheating. Finally, competitive elements can inadvertently favor those with more time, prior knowledge, or faster cognitive processing.

Each educator must decide what will work best for their students. We can soften some aspects of competitiveness by planning activities with no overall winner but rather students competing against themselves to achieve rewards that improve their knowledge, skills, or grades.

Collaboration

Gamified learning works well when you group students into teams. Learners working together towards a common objective can increase everyone’s motivation. Peers teach and learn from one another, supporting students who might otherwise be left behind. All students have opportunities to develop their communication, negotiation, conflict resolution, and leadership skills. Finally, collaborative tasks can reduce student anxiety as teams share successes or failures.

For example, you might set up a game where teams must answer questions or find information to get a clue. Clues help teams determine the overarching object, theme, phrase, concept, technique, or subject. Each team sends a member to the front of the classroom to get a card with a written clue from the teacher. They take the card back to their team and solve the problem. When they figure out the answer to the clue, they write it on the back of the card and take it to the instructor. If they have the clue correct, they get the next clue. When they have collected all of the clues, they have one chance to name the object, theme, phrase, concept, technique, or subject. If they miss it, they return to their group to discuss and try again. However, they only get three chances before elimination.

Risk

Risk is a fundamental element of game design, and it plays a critical role in engagement and motivation. Researchers found that learners are more likely to research the answers to a question-based challenge if they lose points for wrong answers.

Many gamified learning experiences involve making decisions that have consequences within the game, simulating real-life choices, and encouraging critical thinking. Such games offer a safe environment for failure. Risks can lead to “failures” in the game, but these do not carry the same weight as in the real world, reducing the fear of trying and failing something new.

Reward and Recognition

Rewards and recognition for participating and excelling at games take several forms. Points are the most common form of reward. Students can accumulate points and use them for other rewards or benefits. Other forms of reward and recognition involve visual tokens like digital badges or ranking on a leaderboard. Formal acknowledgment, like a specific certification, might carry significance outside the gamified learning environment. Winning a learning game might lead to special privileges like moderating a forum or leading a group discussion.

One strategy that works well in brick-and-mortar classrooms is using poker chips. Students have multiple opportunities to complete learning activities for poker chips. When it comes time for the big exam, students can use these chips to “purchase” extra questions. If the student gets an item wrong on the test but a bonus question correct, they can replace the incorrect item with the correct bonus to improve their score. However, they can only replace incorrect items; they can’t get extra points. This method offers a fun way to incentivize students without disrupting your grading metrics. Students could also use poker chips to buy an extra day to complete a project or a “get out of jail free card” for one late arrival to a class.

Example Games

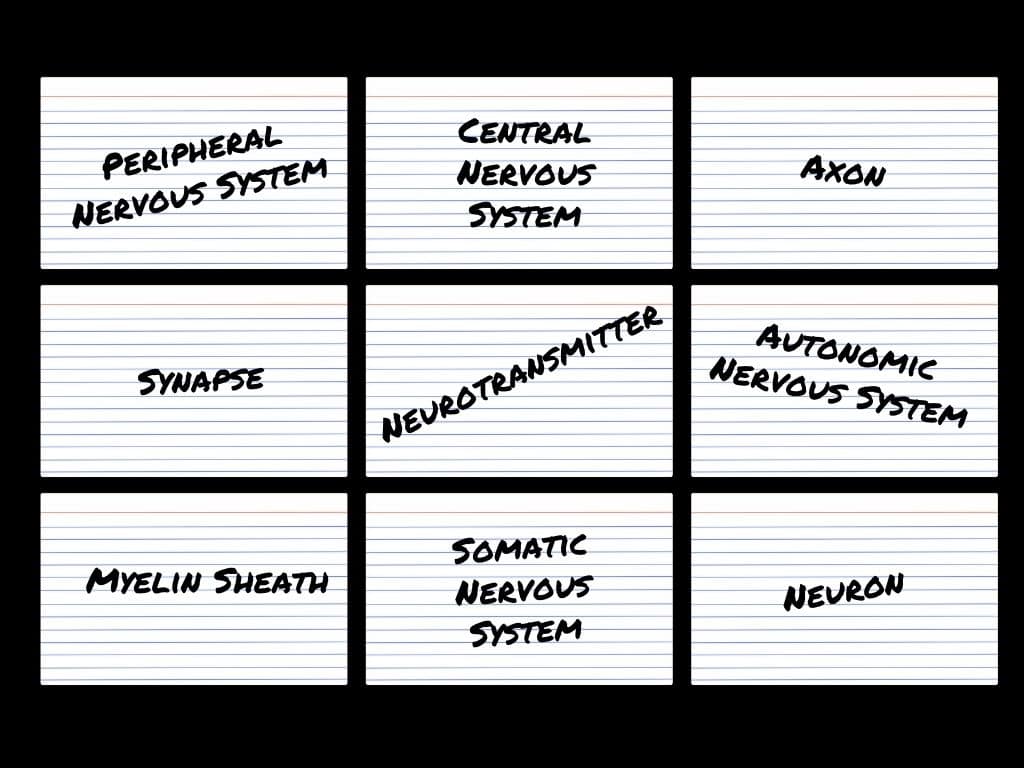

If you’re new to gamified learning, start with familiar games adapted to your classroom content. Classics like Heads Up, Scattergories, and Jeopardy require learners to describe concepts, use anatomical terminology, make connections between concepts, and recall previously learned information.

Heads Up

Heads Up is a game where one teammate describes a previously learned concept to another who must guess what it is against the clock. Each round has ten words worth a point each for the team.

Break your students into pairs. Each team gets four “packs” of ten words each. You create the packs by writing the terms you want students to know on index cards and bundling ten cards with a rubber band into a pack. Each student in the pair gets two packs with four total rounds of play.

During a review phase of six to ten minutes, let students use their textbooks or course materials to review the concepts in their packs. They must know these concepts well enough to describe them to their teammates. Students switch roles each round.

For round one, set a timer for two minutes and 30 seconds (or use a stopwatch). Say “Go!” and one student will describe a concept to the other. When they identify the concept correctly, they take the card and hold onto it. If they identify something incorrectly, the card goes to the back of the deck. Students try to identify as many cards/concepts in a pack as possible in the time allotted.

For round two, set the timer for two minutes. For round three, set the timer for 1.5 minutes; for round four, set the timer for one minute. At the end of the four rounds, teachers give each student a poker chip for each point earned by their team.

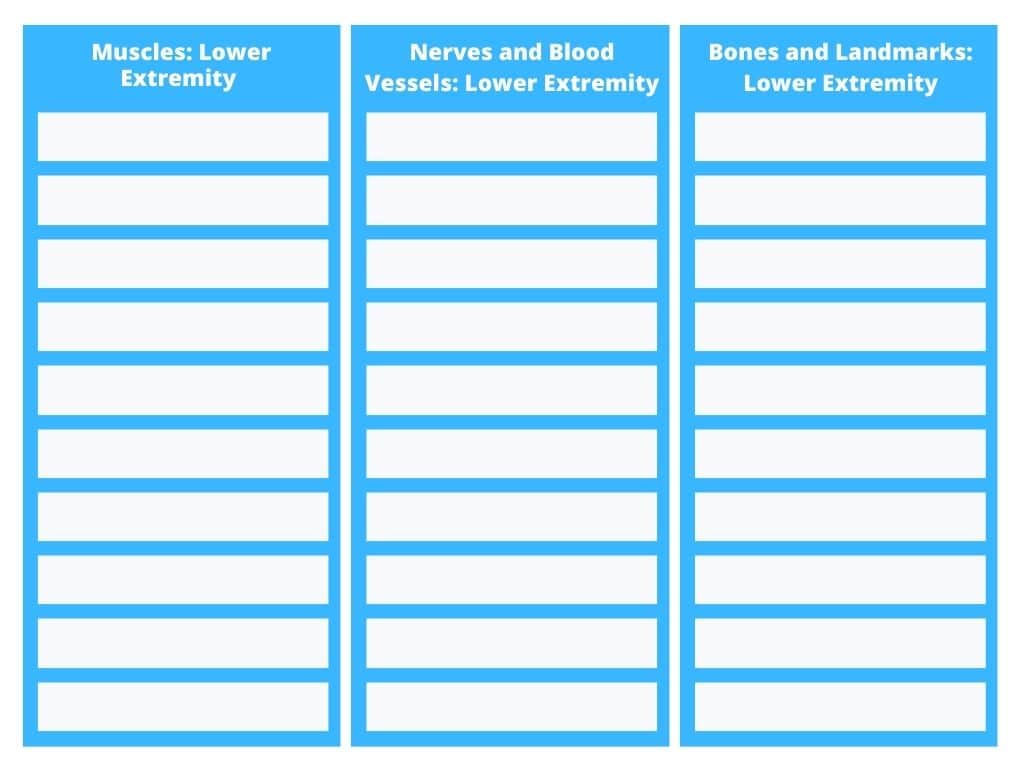

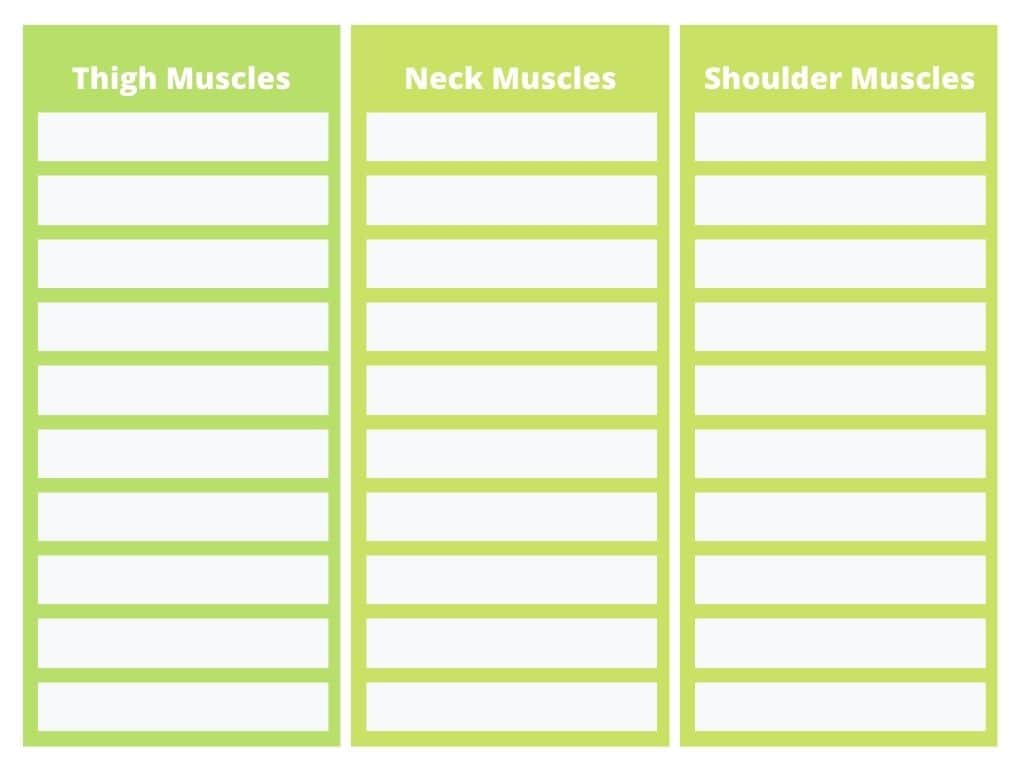

Scattergories

If you’re familiar with the original game, you know that players must complete twelve categories with a single word, all beginning with a predefined letter. Adapt this game to three categories where students identify ten words for each category, as shown in the image examples. You can choose to use a predetermined letter (e.g., all words have to begin with the letter C), or you might allow three letters (e.g., all words have to begin with either a C, F, or S), or you can leave it open. Set a timer for one to two minutes and say, “Go!” when the timer goes off, have students count up their points (half a point for each correct word) and turn them in for poker chips to use for a later reward.

Learning Passport

With a learning passport, the teacher creates a series of activities students complete throughout a term. As they complete each activity, they turn in proof to receive a stamp in their passport. At the end of the term, they show their stamps for bonus questions for the final exam (as discussed previously).

Learning passports have the advantage of not being competitive, allowing students to work at their own pace, and offering various learning activities. For example, you might get a stamp for receiving a massage in the student clinic or for giving a massage to a teacher for detailed feedback. You could get a stamp for compiling a Pinterest board of web-based massage resources or making a social media video comparing and contrasting lubricants. Alternatively, the passport might outline five student-chosen goals mixed with instructor-selected activities. Learning passports are an easy way to add a little bit of gaming to motivate students to dive deeper into the course content.

In Closing

In closing, we’ve learned that gamified learning uses gaming elements and game-design principles to engage and motivate students in nongame contexts. We’ve discussed the benefits and challenges of gamified learning, the principles and components of gamification, and example activities emphasizing teacher-created content for brick-and-mortar classrooms. Readers might also enjoy An Overview of Peer Learning in Adult Classrooms and An Introduction to Social Media in Massage Classrooms for related content.