Harnessing the Power of Rubrics for Hands-On Skill Learning

RUBRIC DEFINED

A rubric is a scoring guide used to evaluate the performance of a skill, a task, or a project. Rubrics for hands-on skills outline the observable criteria for work, which are “excellence,” “good,” or “needs improvement.”

In massage education, we typically use rubrics as assessment tools for scoring student performance of hands-on skills. Rubrics communicate explicit criteria for the ideal, acceptable, or unacceptable performance of bodywork techniques, allowing for fair, reliable, and consistent grading. However, when we view rubrics as integral to the learning process, they significantly enhance our teaching clarity and the quality of student work.

In this article, we’ll discuss subjective and objective measures. Next, we’ll write individual skill rubrics and integrate them into a rubric to measure the performance of a bodywork form. We’ll talk about multiple ways to use rubrics in massage classrooms.

Objective Verses Subjective Measures

I’m facilitating a teacher training on rubrics, and I ask the group to describe the ideal application of an effleurage stroke. One teacher says, “The stroke should be relaxing and fluid,” and most of the group nod in agreement. I quarry further and say, “If I’m grading the student, how will a perfectly applied relaxing stroke look to me as an outsider? What does a fluid stroke look like?” A different teacher says, “The stroke will look smooth and soothing.” Again, nods of agreement. I say, “What does smooth look like to an outsider? How do I know the stroke is fluid?”

The teachers think about my words and ask themselves, “What does smooth look like? What does fluid look like to an outsider?”

I ask, “Have any of you experienced petrissage strokes that feel relaxing, fluid, and soothing?” I see nods of “yes.” “What about pin and stretch techniques or a crossed-hands stretch used in myofascial release? Does anyone find these techniques relaxing and soothing?” I see nods of “yes.” “What about rocking techniques? I find jostling, shaking, and rocking to be very relaxing. Does anyone else find these types of techniques relaxing and soothing?” I see nods of “yes.”

What we learn from this discussion is that “relaxing,” “fluid,” “smooth,” and “soothing” don’t accurately define an effleurage stroke because they are subjective measures based on our personal opinions, interpretations, points of view, and judgments.

A rubric outlines performance criteria based on objective measures. Objective measures are factual data that are observable and measurable independently of the individual making the assessment. In other words, an outsider (someone other than the therapist or the client) could look at five different therapists applying effleurage and evaluate their performance accurately because of what they see.

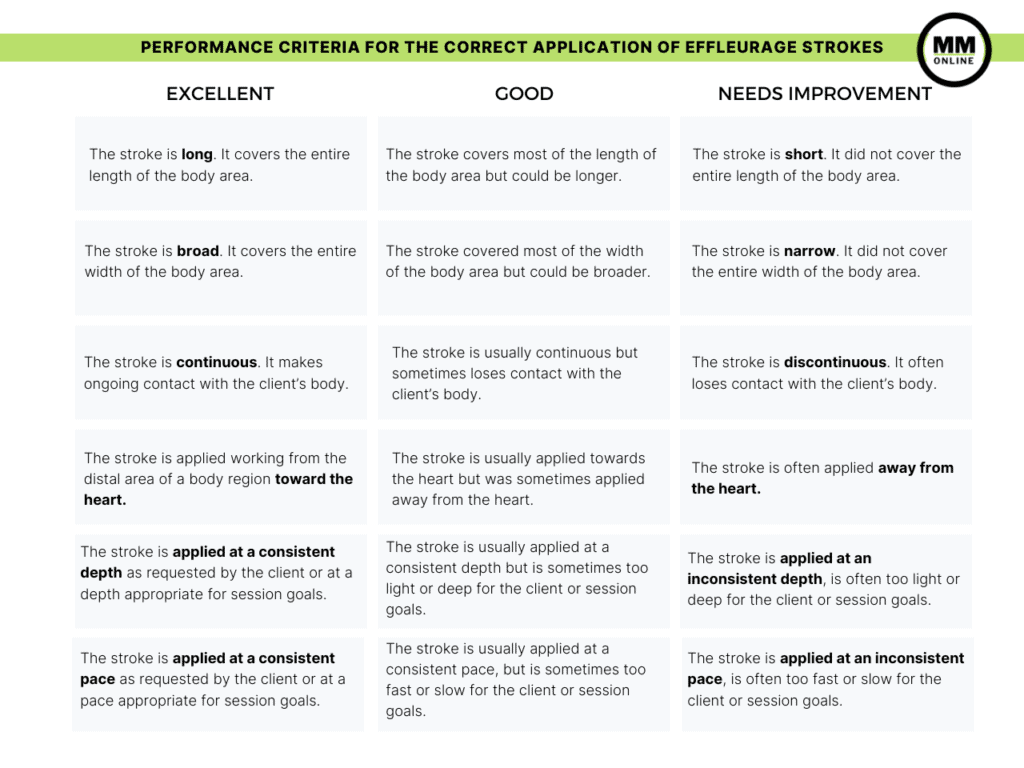

The Objective Criteria for an Effleurage Stroke

Let’s break down the objective criteria for the proper application of an effleurage stroke. When we watch an expert massage therapist delivering a textbook effleurage stroke, we observe that:

- The stroke is long. It covers the entire length of a body area.

- The stroke is broad. It covers the entire width of a body area.

- The stroke is continuous. The therapist’s hands make ongoing contact with the client’s tissue.

- The stroke is applied working from the distal area of a body region towards the heart.

- The stroke is applied at a consistent depth as requested by the client or at a depth appropriate for session goals.

- The stroke is applied at a consistent pace as requested by the client or at a pace appropriate for session goals.

Rubrics place these objective measures alongside descriptions of work that is acceptable but not ideal and work that is not acceptable and needs improvement.

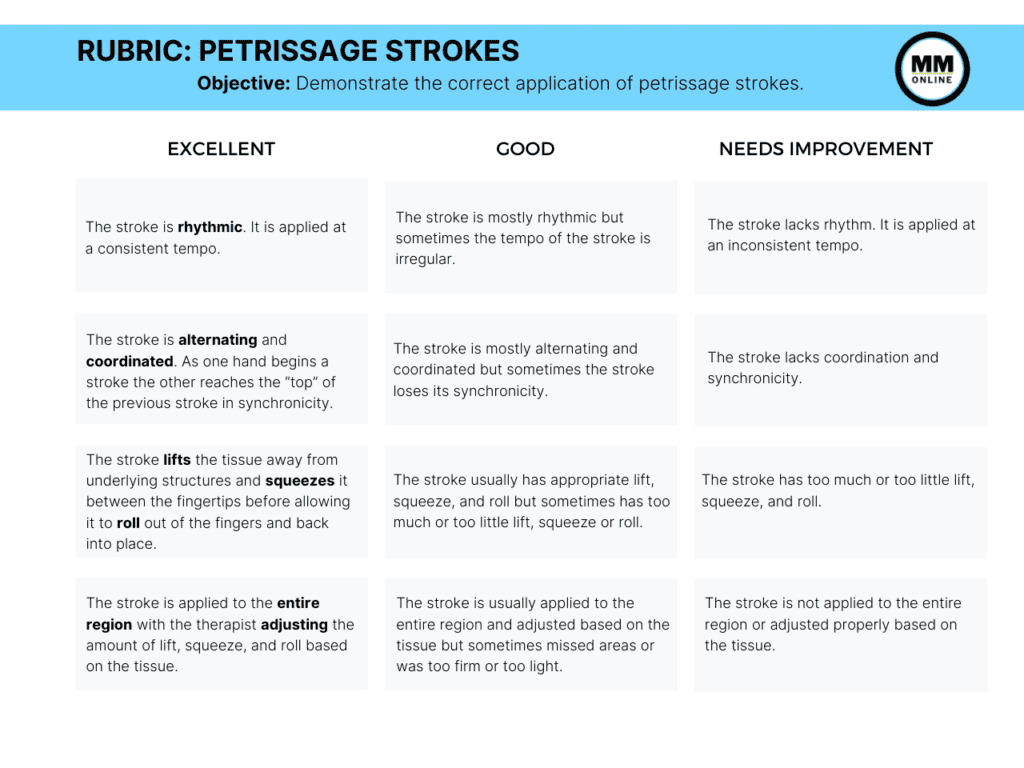

The Objective Criteria for a Petrissage Stroke

Now, let’s identify the criteria for properly applying petrissage strokes. Again, we want to imagine an expert massage therapist delivering a textbook petrissage stroke. We’ll observe that:

- The stroke is rhythmic. It is applied at a consistent tempo.

- The stroke is alternating and coordinated. As one hand begins a stroke, the other reaches the “top” of the previous stroke in synchronicity.

- The stroke lifts the tissue away from underlying structures and squeezes it between the fingertips before allowing it to roll out of the fingers and back into place.

- The stroke is applied to the entire region, with the therapist adjusting the amount of lift, squeeze, and roll based on the tissue. For example, firm petrissage with significant lift and squeeze is appropriate for fleshy areas, while the fingertips might apply gentle petrissage to the eyebrows.

As you know, therapists categorize skin rolling, fulling, and wringing as types of petrissage in classical Swedish massage. In foundational classrooms, it’s best to treat stroke variations as unique techniques until students are proficient with an entire massage form. Otherwise, students typically default to using only the primary expression of a technique. Ideally, you’ll write rubrics for skin rolling, fulling, and wringing and teach them with the same emphasis as petrissage.

As with effleurage, we’ll place these objective measures alongside descriptions of work that is acceptable but not ideal and work that is not acceptable and needs improvement.

The Role of Rubrics in Hands-On Skill Development

Now that we better understand what rubrics are and how they work let’s examine the role of rubrics in skill development.

Establish a Standard

When you work with massage teachers, you often hear a similar story. Instructors teaching later modules or terms report that different cohorts of students trained by different instructors demonstrate dissimilar foundational skills. This group has strong draping skills but forgets to use bolsters, while this other group can’t put together a Swedish massage but knows how to use active isolated stretches (which aren’t taught in the curriculum).

It’s relatively common to find that most schools don’t define established standards for hands-on skills. Instructors teach techniques the way they learned them – sometimes incorrectly. For instance, I learned friction techniques incorrectly and passed on faulty methods to students for over a year until a senior instructor corrected me. Additionally, instructors tend to teach methods they like and use in their private practices effectively and methods they don’t like or use ineffectively or not at all.

When faculty members work together to establish objective measures for techniques and teach from the same rubrics, these inconsistencies disappear, and graduates demonstrate stronger hands-on skillsets. However, there must be a determined effort to bring teachers together, define techniques objectively, correct faulty understanding, and agree to adopt standardized rubrics.

Clarify Expectations

Use rubrics during technique demonstrations and as a pre-assessment before practical exams to clarify your expectations. Rubrics give students insights into aspects of grading and scoring that would otherwise be ambiguous and confusing. Rubrics require instructors to define their criteria for excellence in specific terms so students understand how they must perform to achieve high grades. This clarity allows them to prepare effectively and practice efficiently.

Enhance Observation and Imitation

Effective hands-on skill instruction recognizes that learners observe and imitate everything they see a teacher do. Rubrics make subtle movements of the teacher’s hands and body noticeable so that students are less likely to misinterpret movements and develop incorrect patterns.

Ideally, teachers demonstrate each criterion of a rubric and then contrast it with the same aspect of a technique performed incorrectly. For example, when teaching petrissage, the teacher might say, “This is a petrissage stroke. You’ll notice that petrissage is rhythmic. The stroke is applied at a consistent tempo. If a petrissage stroke lacks rhythm it looks like this. Can everyone see the difference between a rhythmic stroke and a stroke that lacks rhythm?”

“You’ll also notice that petrissage is an alternating and coordinated stroke. As one hand begins a stroke the other reaches the “top” of the previous stroke in synchronicity. Let’s contrast this proper application with a stroke that lacks coordination and synchronicity. Do you see the difference?”

Improve Self-Assessment and Feedback

Rubrics guide students during practice sessions and provide a tool for self-assessment and feedback. Because they are specific and objective, peers know how to phrase their feedback in words everyone understands. For example, a student acting as a client can feel that an effleurage stroke is too short or narrow or that a petrissage stroke lacks lift and squeeze. Instead of saying, “The stroke feels too gentle,” they reference the rubric and say, “The stroke doesn’t have enough lift and squeeze.”

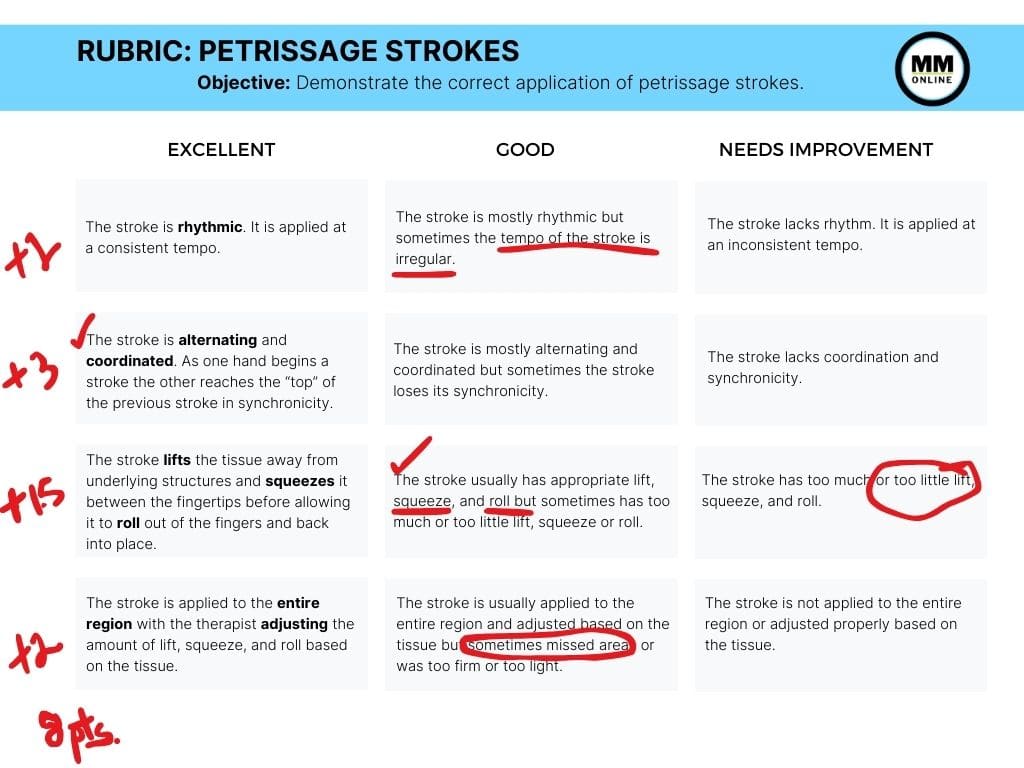

Ensure Fair Assessment

Many schools bring in former students, teaching assistants, and other teachers during midterm and final practical examinations. Rubrics ensure consistency in evaluation to improve fair grading. Instructors should review rubrics with testers to ensure they understand the performance criteria using a demonstration body to contrast excellent skills with those that need improvement. One way to manage this process is to ask testers to be present at the final practical review you conduct with students. Now, everyone is on the same page. Testers can make brief notes on scored rubrics to defend the scores they gave a particular student, as shown in the image above.

Guidelines for Writing Individual Technique Rubrics

As discussed previously, an individual technique rubric outlines the objective criteria for separate skills, such as effleurage and petrissage. The first step to creating this type of rubric is to identify the essential, observable components of the skill and make a list as we did with effleurage and petrissage. It helps to imagine or watch an expert massage therapist apply a textbook stroke to a practice body and describe what one sees without subjective language.

It’s also important to recognize and eliminate adaptations a therapist makes to a stroke based on their personal style. You want to capture the essence or “heart” of the core stroke.

Once you have a list of observable criteria, scrub it for subjective language. Subjective words often used in massage therapy include relaxing, soothing, fluid, invigorating, smooth, elegant, graceful, refreshing, and so forth.

Now, place your criteria in a table and define acceptable but not ideal and unacceptable work that needs improvement, as shown in the examples. Share your rubric with other teachers to get their feedback, or work in faculty teams to develop rubrics for your school.

Guidelines for Writing Integrated Rubrics

An integrated rubric outlines the objective criteria for all the strokes in a particular massage system, plus the other skills required to demonstrate proficiency during a session. For example, you might describe the objective criteria for the performance of these skills for Swedish Massage:

- Equipment set up and session room organization

- Use of bolsters and client positioning

- Draping skills

- Use of lubricant

- Opening the massage

- Effleurage

- Petrissage

- Friction

- Tapotement

- Vibration

- Joint movement

- Closing the massage

- Time management

When you write the criteria for each skill, you lift a consolidated description directly from each skill rubric. So, we describe effleurage like this: Effleurage strokes are long, board, continuous, directed towards the heart, and applied at a consistent depth and pace. The individual skill rubric defines and clarifies each item I’ve placed in bold type (see the effleurage rubric for clarity).

The petrissage entry might state: Petrissage strokes are rhythmic, alternating, coordinated, and applied with appropriate lift, squeeze, and roll to the entire region while adjusting for the tissue (see the petrissage rubric for clarity).

Rubrics Take Thought and Effort

Writing rubrics requires thought, effort, and skill because most of us have used subjective criteria to judge common techniques since we were students. You may realize that improving skill teaching with rubrics at your school will take a concerted faculty effort. Ideally, an administrator would assign individual skills to teams of two instructors working together. These pairs would write a first draft rubric for their assigned techniques. Next, teams exchange with others who critique and adjust rubrics to reduce subjectivity. Finally, teachers need to get into a room with a practice body and test the rubrics through application and observation. If we are willing to make an effort and teach from rubrics consistently, we’ll find that our students reward us with better skills.

In Closing

Rubrics are more than just assessment tools; they are integral to learning, especially in teaching hands-on skills. By providing clear criteria, consistent assessment, and valuable feedback, rubrics empower students to master practical skills effectively. The careful design and implementation of rubrics can significantly enhance the teaching and learning of hands-on skills, paving the way for students to achieve proficiency and excellence in their practical endeavors.