Teach Students to Study On The Go With These Proven Tips

Introduction

Massage instructors know that their adult learners have multiple responsibilities. Most have full-time or part-time jobs, some have children or aging parents, and many have social groups that are important to them. Learning must slot into the margins of adult lives to be practical. Even when students attend all their classes, their grades may suffer if they can’t find enough time for out-of-class review. For more than 100 years, education researchers and cognitive psychologists have pointed to shorter study segments as one way to improve content learning. Let’s look at the background and encourage students to study on the go.

The Forgetting Curve

In 1885, Hermann Ebbinghaus introduced the concept of “the forgetting curve” in “Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology.” In this groundbreaking work, Ebbinghaus described the first empirical studies on memory and information retention, laying the foundation for modern memory research.

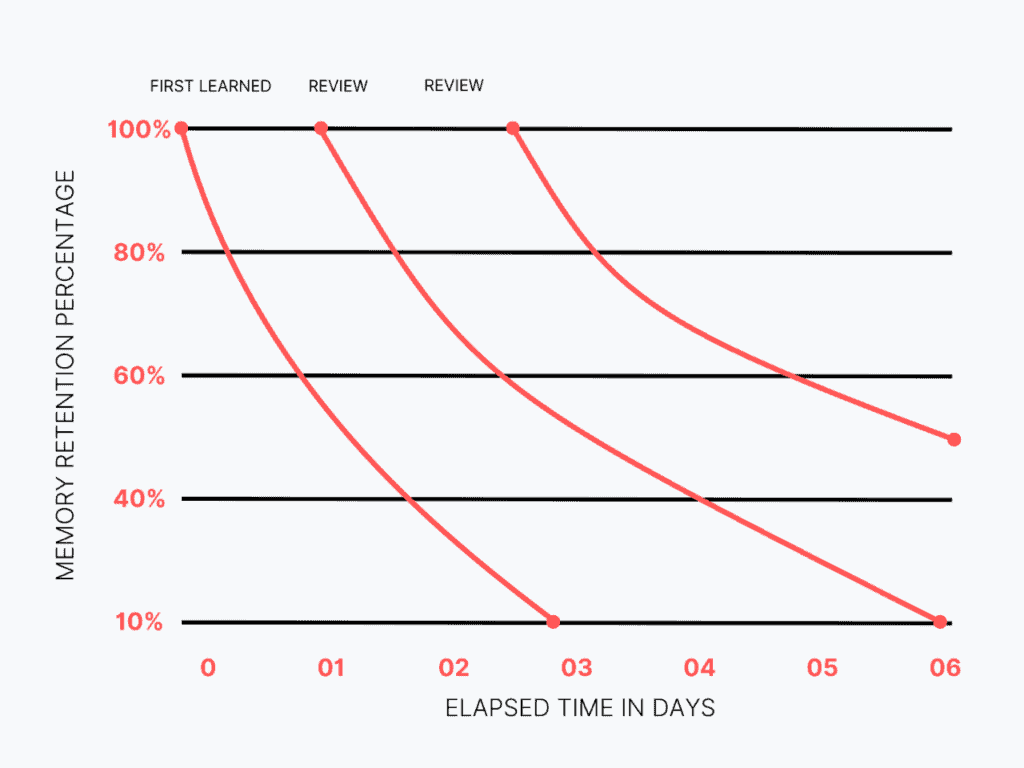

The forgetting curve illustrates the decline of memory retention over time. Ebbinghaus discovered a steep, significant decline in information retention soon after learning. The curve gradually flattens out, indicating that memory loss decreases over time. The traces of information retained after the initial loss remain resilient. Additionally, each time a person revisited or repeated information, the forgetting curve for that information was less pronounced, leading to increased retention over longer periods. Ebbinghaus found that the initial strength of the memory and how well a person encoded it through comprehension and active learning played a role in how quickly they forgot information. Memories tied to emotions or reinforced through learning activities and quizzing tend to deteriorate more slowly.

Spaced Practice

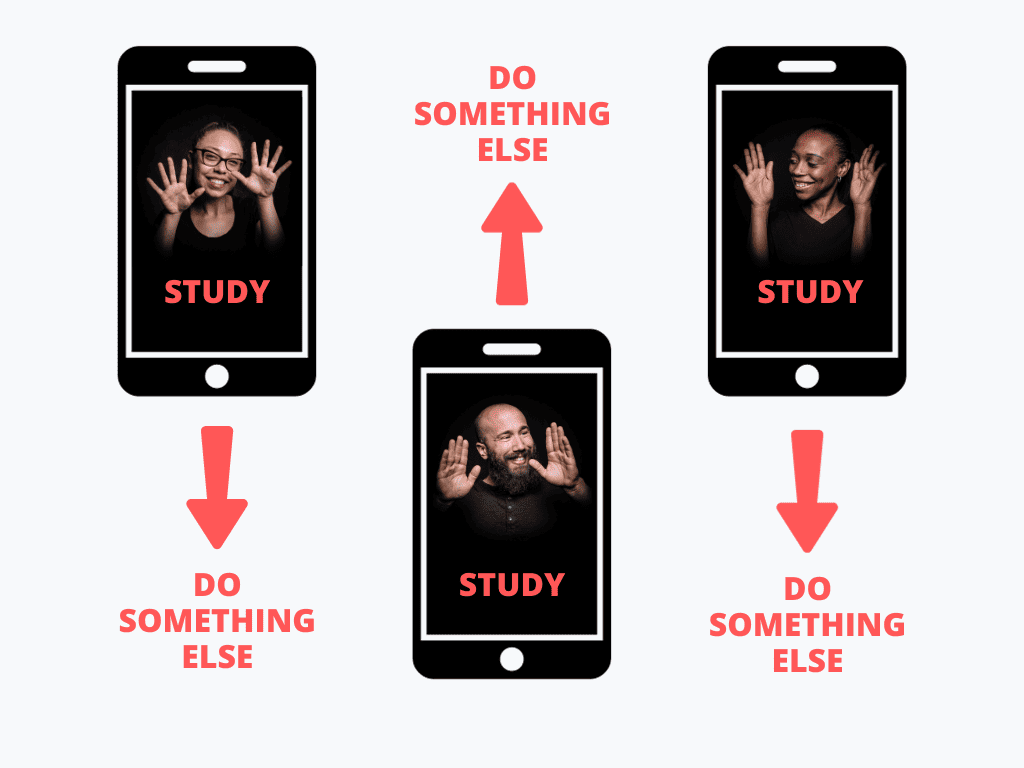

Using Ebbinghaus’s research, C.A. Mace introduced the concept of “spaced practice” in his book “Psychology of Study,” published in 1932. Today, instructional designers continue to advocate for spaced practice, calling it by several names, including spaced repetition, information rehearsal, distributed practice, and drill and practice. In spaced practice, learners study information during short five to ten-minute sessions using flash cards or short quizzes, then go away and do something else, only to return for another short study session. Students return to information for review at ever-increasing intervals to enhance memory retention and recall.

Chunking

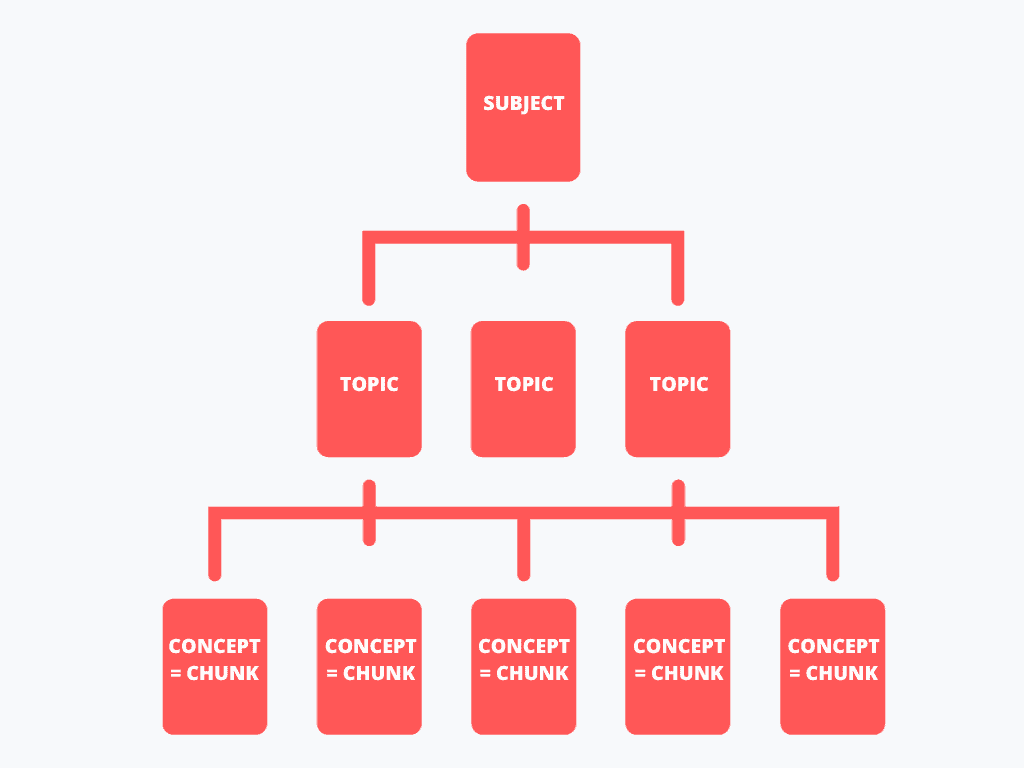

In “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information,” American psychologist George A. Miller introduced the concept of “chunking.” Miller proposed that a person’s working memory can simultaneously hold about seven (plus or minus two) items. He suggests that the human brain has a limited capacity for processing and storing active information. We can improve cognitive processing and information recall by grouping individual bits of information into larger, meaningful units.

Educators often use learning a phone number to provide an example of Miller’s principles of chunking in action. Consider a 10-digit phone number – 3230817985 – presented as a long string of digits. It’s challenging to process and remember. Now, break the number into smaller units: 323-081-7985. When we break phone numbers into an area code, middle segment, and four-digit ending, we find them much easier to understand and remember. Chunking works because it reduces cognitive load, creates meaningful patterns, and utilizes existing knowledge.

In adult education, we can apply chunking by looking for ways to make complex or voluminous content more manageable and memorable for learners. For example, we can break down long text sections into short paragraphs illustrated with diagrams and images, divide complex processes into step-by-step procedures, and group related concepts together during lessons.

At Massage Mastery Online, we incorporate chunking principles into the lesson and topic structure we’ve adopted for our textbooks. Within topics, we use lots of headings, subheadings, and images to help learners understand the hierarchy of the content. We use a short paragraph structure, define words in the context of the paragraph, and use bullet points whenever possible. We can improve student engagement and comprehension by approaching content with Miller’s principles.

Microlearning

By 2010, the terms “microlearning,” “just-in-time learning,” and “learn-on-the-go” were established in learning theory and instructional design. The increasing use of smartphones and the rise of social media introduced people to the appeal of short-form videos. Information presented in compact, focused segments became popular in the corporate world as companies sought efficient ways to train their employees.

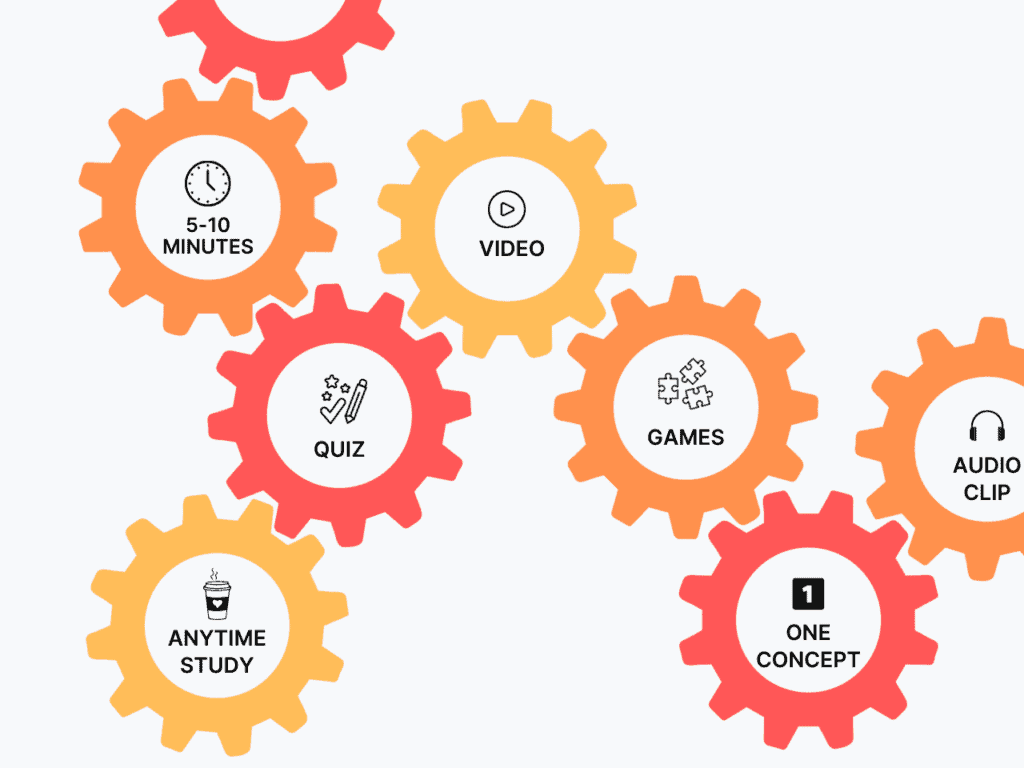

The concept of microlearning aligns with cognitive research that suggests learners are developing shorter attention spans and feel overwhelmed by long educational sessions. As a result, instructional designers are turning to methods that reduce cognitive load. For example, instruction might take the form of:

- Concise instructional videos that focus on one topic at a time.

- Digital flashcards for drilling terminology and concepts.

- Short, online courses featuring video, audio clips, learning games, and quizzes.

- Infographics representing data in bite-sized chunks.

- Interactive learning games that provide immediate feedback on student responses.

While microlearning has proven successful as a system for corporate training, language learning, and casual self-development, it hasn’t worked as a format for formal adult education. However, microlearning methods are ideal for on-the-go study sessions. Researchers say that five-to-ten-minute study sessions improve learning outcomes when students use them consistently.

When Learning is a Swipe Away

Previously, we acknowledged that our students are pulled in multiple directions by jobs, families, and social groups, so scheduling out-of-class study time is challenging. Researchers say that five-to-ten-minute study sessions improve learning outcomes when students use them consistently. So, what’s stopping students from studying while they wait to pick up their kids from school or watch their pet frolic from a bench at the dog park?

It’s that big, heavy textbook. No one in their right mind is dragging that thing all over town.

Enter digital textbooks, which are perfect for microlearning study sessions. Watch a video, listen to a topic, read the captions on images, drill with digital flashcards, play a learning game, or take a practice quiz to review course content.

Today’s students live on their phones, and now their textbooks do too, so they can study while they ride the bus to school, wait for a friend at a café, or take a break at work. If learning is just a swipe away, you’re more likely to study in the margins of your life – a practice that significantly improves academic scores.

In closing, we’ve discussed the forgetting curve, spaced practice, chunking, and microlearning methods. While these educational methods can help us plan content for effective classroom instruction, they are even more critical for on-the-go study.