Embracing Growth: Carol Dweck’s Growth Mindset and Its Application in Adult Education

Carol Dweck’s groundbreaking work on mindset changed how we understand learning and intelligence. At the heart of her decades-long research is the concept of the “growth mindset.” Unlike a fixed mindset, where individuals believe their abilities and intelligence are static traits, a growth mindset thrives on challenge. People don’t view failure as evidence of unintelligence but rather as a springboard for self-development. In this article, we discuss the origins of Dweck’s theory, examine the benefits of teaching the growth mindset to students, and integrate Dweck’s principles into our massage classrooms.

The Origins of the Growth Mindset: Carol Dweck’s Early Research

Psychologist Carol Dweck became interested in students’ attitudes about failure. She was intrigued by the different reactions individuals had when faced with challenging tasks.

For example, one of Dweck’s seminal studies involved observing how schoolchildren dealt with failure. In this study, teachers gave children a series of puzzles to solve. Initially, the puzzles were relatively easy but gradually became more difficult. Dweck noticed that some children relished the more complicated puzzles, viewing them as opportunities to learn, while others became demoralized when they could no longer solve the puzzles quickly.

A fundamental discovery in Dweck’s research was the realization that people’s beliefs about their abilities played a crucial role in how they dealt with challenges. She noticed that individuals who believed their intelligence and abilities were fixed traits (a fixed mindset) were less likely to persist in the face of difficulties. In contrast, those who saw their abilities as malleable and capable of development (a growth mindset) were more resilient.

Another significant aspect of Dweck’s early research was exploring the impact of praise on children’s development. She found that praising children for their innate abilities, such as being smart, actually made them less likely to take on demanding tasks in the future. They feared that failing would make them seem less intelligent. In contrast, children praised for their efforts were more likely to seek challenges and persist in the face of complications.

These early studies were crucial in forming Dweck’s theory of the growth mindset. She began to understand that encouraging a belief in the malleability of intelligence and abilities could significantly impact how individuals approach learning. This understanding laid the foundation for her later work, where she more fully developed and articulated the concept of the growth mindset for children, adult students, athletes, leaders, and people interested in self-development.

Research Outcomes in Education

Dweck posits that people develop intelligence through effort, strategies, and help from others. Her concept of malleable intelligence challenges the traditional view that intelligence is an innate trait fixed at birth. An important aspect of her research was measuring academic results after teachers taught students about brain plasticity.

When Dweck and her research team began teaching a growth mindset to children, the results were profound. They showed that changing students’ beliefs about their intelligence could significantly impact their academic performance, attitudes toward learning, resilience in the face of strenuous tasks, and overall educational experiences.

Research indicates that adults who adopt a growth mindset can experience changes similar to those seen in children, such as increased motivation, resilience, and a greater willingness to engage in lifelong learning. However, adults often have more entrenched beliefs that can influence their mindset. Changing these established perceptions requires targeted interventions and consistent reinforcement.

Attributes of Growth Mindset and Fixed Mindset

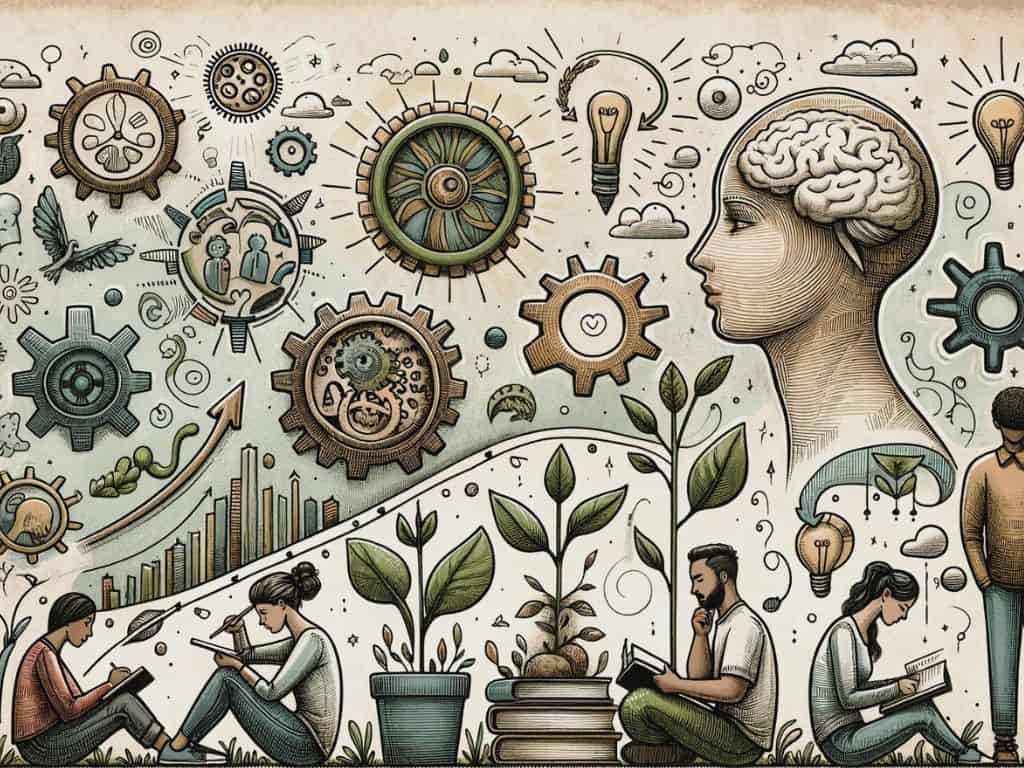

The growth and fixed mindsets represent two ends of a spectrum in terms of how individuals perceive their abilities and approach learning and challenges.

Growth Mindset:

- The belief that people can develop their intelligence and abilities through effort, new strategies, and instruction.

- Approach to life is dynamic and adaptive by continuously seeking self-improvement and life-long learning.

- View challenges and failures as opportunities to learn and grow.

- Considers effort as a path to improvement, mastery, and success.

- Welcomes constructive criticism and feedback as a means to improve.

- Feels inspired by the success of others and uses others’ success to learn.

Fixed Mindset:

- Belief that intelligence and abilities are innate traits that one cannot significantly change.

- Approach to life is static by maintaining comfort zones. May plateau early in personal and professional development.

- Avoids challenges to prevent the appearance of unintelligence.

- Views failures as a reflection of unchangeable abilities. May feel overwhelmed or helpless.

- Considers effort as futile if one is not naturally good at something.

- Ignores feedback or takes it personally by viewing it as a critique of their inherent abilities.

- Feels threatened by the success of others and sees it as highlighting their own limitations.

Implementing the Principles of Growth Mindset in Adult Education

Educators who learn about and embrace the growth mindset philosophy often change their teaching methods to focus less on innate ability and more on encouraging effort and perseverance. Explore these six principles and how they function in your classroom:

Teaching Brain Plasticity

Dweck suggests educators teach students a short course on brain plasticity to jump-start a growth mindset in classrooms. As educators, we know that brain plasticity (neuroplasticity) is the brain’s ability to change and adapt in response to effort and experience. It occurs at multiple levels, ranging from strengthening synaptic connections between neurons, forming new synaptic connections, and consolidating memory through the hippocampus. Educators can find examples of growth mindset and neuroplasticity curricula when they search on the Internet.

The Power of Yet

One of the simplest but most powerful ways to foster a growth mindset in adults is through the language we use during learning processes. When learners struggle, we can encourage resilience and effort by adding “yet” to their statements. For example, an instructor can amend a student’s frustrated declaration of “I don’t understand how the nervous and muscular systems interact” to “You don’t understand how the nervous and muscular systems interact yet.” This subtle linguistic shift emphasizes the potential for learning and growth and helps instructors suggest a learner’s next steps. For instance, the instructor might say, “I want you to explore pain perception and what muscles in a region do when an injury causes pain. After reading about this interaction, write about your findings in no more than 500 words, and I’ll give you five extra credit points for your effort.”

Value Process Over Outcome

Often, teachers praise students for their grades on assignments or exams. When we adjust our communication to focus on student efforts and strategies, we encourage them to engage more deeply with the material. For example, we can ask students to describe the methods they used to prepare for an exam, how many hours they spent, and how their efforts manifested in their success or failure. We won’t praise good grades or criticize poor grades. Instead, we’ll ask learners to think about adjusting their tactics to prepare for the next exam and learn more effectively.

We can also praise students for their approach to activities or projects. For example, “I see that you’ve made flashcards and you’re using them to study between classes. Making flashcards and studying in spare moments are excellent learning strategies,” or “I appreciate that you approach classroom activities with a positive attitude. You try hard and I see how it impacts your growth.”

Choose Effort Over Easy

Many students are inspired when we share stories of people who overcame obstacles or worked hard to succeed. We can help students create positive associations with effort by offering opportunities to choose challenges. For example, have students work in pre-determined pairs to complete a study guide project. Offer them a choice between an easy project for 3 points, an intermediate-level project for 5 points, and a challenging project for 10 points. Cheer for the students who opt for the challenging project.

Choose Risk Over Safety

In adult learning contexts, “risks” take various forms. Trying anything new takes students out of their comfort zones, as does voicing opinions and ideas in discussion groups. Tackling complex, real-world problems that don’t have straightforward solutions can be risky, as it involves the possibility of making mistakes or wrong choices.

Educators can encourage risk-taking by exploring incorrect answers and poorly applied techniques. For example, during an exchange, we can say, “Without hurting your client, I want to see the worst application of petrissage you can deliver. Make it horrible! Make it really, really bad! Great! This is the worst petrissage I’ve ever seen. Now, I want you to share what makes this petrissage bad.” Permitting themselves to misapply a technique helps students release fear. It also helps them identify the attributes of a poorly applied technique. You learn a lot about good by exploring bad.

We can take a similar approach to incorrect information. For example, when we process a midterm exam with students, we might say, “Several of you answered question 8 incorrectly, and it made me curious about your thinking processes. Let’s discuss how a person might arrive at option B or C, which are wrong answers. Talk it over with the person next to you, and then I’ll ask you to share your ideas.”

Exploring incorrect answers requires critical thinking that helps learners fill in knowledge gaps. It also encourages risk-taking because your attitude as the teacher is that a wrong answer is an indication – not of lack of intelligence – but a gap in a thinking process.

Provide Constructive Feedback

As teachers, we want to offer feedback on how students can approach learning tasks more effectively or revise their work to improve it. This type of feedback encourages resilience and persistence. We can also teach our students how to give and receive peer feedback, which we discuss in an upcoming Massage Classroom Coach session.

Celebrate and Reflect

We want to acknowledge and celebrate when learners take risks. This recognition can be a powerful motivator and reinforces the idea that risk-taking is integral to self-development. Prompting learners to reflect on their learning experiences, especially in instances where they took risks or didn’t have the outcome they wished, helps them recognize that learning is a process.

In Conclusion

By understanding and implementing the principles of Carol Dweck’s growth mindset into adult learning environments, we can create a dynamic, resilient, and motivated community of learners. A growth mindset enhances the learning experience and prepares our graduates to face the challenges in their professional lives.

Related Posts

Motivating adult learners can be challenging. You put time and effort into your curriculum only...

In the world of massage education, a new chapter is unfolding, one that integrates technology...

A Discussion with Special Guest, Whitney Lowe and the Results of the Assessment Survey Introduction...