Teaching Ethics Through Scenarios and Why You Care!

Introduction

Ethics education in massage therapy is about preparing students to navigate the messy, complicated, real-world situations they’ll encounter in practice, like those moments when a client makes an unexpected request, when they feel uncertain about how to respond, or when their own biases and assumptions surface in ways they didn’t anticipate.

That’s why scenario-based learning is so powerful. It bridges the gap between theory and practice, giving students the chance to wrestle with ethical dilemmas in a low-stakes environment where they can make mistakes, test their reasoning, and learn from their peers.

To accompany the new ethics book I’m working on, I’m creating an entire ready-to-use curriculum to make teaching this challenging topic easier.

In this post, I want to share three scenario-based activities from the Ethical Foundations unit to give you a sense of how scenarios can transform ethics education from abstract concepts into practical, actionable wisdom.

The three activities below demonstrate different ways to use scenarios in your ethics classroom. Each one creates opportunities for peer discussion, critical reflection, and thoughtful decision-making that helps students internalize ethical concepts and carry them into their professional lives. Use these as inspiration for your own materials.

Activity 1: Scenario Stations

Duration: 40 minutes

Goal: This activity aims to place core ethics concepts in real-world settings. Students must defend their reasons for choosing an option, thereby using critical reasoning skills. In addition, students must verbalize their thinking. Verbalization of content leads to better concept formation and recall ability.

Instructor Directions:

Print the scenario posters and student directions (download below). Post a copy of the directions with each scenario poster. On the back side of the scenarios, write in the answers to the questions. Page 2 = A, 3 = B, 4 = C, 5 = B, 6 = C, 7 = B, 8 = A, 9 = B.

Depending on the number of students in your class, tack the scenario posters in different locations (stations) around the classroom before the class begins.

Break students into small groups of two to four people, depending on your class size. Assign each group a starting station.

Explain the activity: Students follow the directions at each station. They have six minutes to complete the task outlined in the directions. When it’s time to move on, student groups travel to the next station to their right. When students have visited all the stations, they’ll return to their seats to discuss their findings.

Once groups are in their stations, say “start!” and set a timer for 6 minutes. When the timer goes off, students travel to the next station. You say “start!” and set the timer for another six minutes, and so forth, until students have visited all five stations.

During the activity, travel to different groups and ask them about their discussion. Deepen the learning by inviting them to consider and discuss related concepts.

When students have visited all of the stations, ask them to return to their desks and identify something they learned about ethics from the activity. Ask several people to share their findings.

Activity 2: Is This Fair?

Duration: 10 minutes per scenario

Goal: This activity utilizes short scenarios to challenge students to consider fairness, equality, and nondiscrimination in the context of massage therapy. Students consider real-world situations in which therapists may feel uncertain or biased about working with specific clients. The Think-Pair-Share format ensures all learners have time to process, articulate, and test their ideas before the class discussion.

Instructor Directions:

Set Up: Have students form small groups of three or four people. Inform students that each client-therapist scenario raises questions about what constitutes fairness in a massage practice. Their job is not only to say what they would do but also to explain why.

Read one scenario aloud: Give student groups 4-5 minutes to discuss the scenario and what they would do if they were the therapist in a similar situation. Encourage them to discuss their differences of opinion respectfully.

Share: Invite 1-3 groups to summarize their ideas.

Key Points: Conclude the discussion by summarizing the key points from each scenario and relating them to the students’ ideas.

Repeat: Continue through as many scenarios as time allows.

Wrap Up: Summarize the activity by noting that fair and equal treatment is not optional. Treating people equally is at the heart of both professional ethics and human rights. Therapists may specialize, but they may not discriminate. Every client deserves respect, dignity, and safety in the massage setting. As long as it is safe for the client to receive massage and they are following reasonable business policies, we provide the best possible care to every client.

Sample Scenarios

Scenario 1: Sarah’s massage business caters to athletes, so she is confused when an overweight and unhealthy client comes into her clinic. Because her business name is Massage for Athletes, Sarah feels she has the right to refer the client to a different massage business. What do you think?

- Key Point: Marketing focus does not override ethical obligations. Turning clients away based on appearance or fitness level is discriminatory. Therapists may define their specialties, but they must still treat clients fairly and respectfully.

Scenario 2: Jasmine specializes in prenatal massage. A man calls to schedule an appointment, and Jasmine immediately says, “Sorry, I only work on women.” She thinks she should not be required to work with men since most of her practice is women-focused. What do you think?

- Key Point: Therapists may have practice specialties, but cannot deny service based solely on sex or gender. Professional ethics require nondiscrimination. Referring out is appropriate only if the client’s needs fall outside the therapist’s competence.

Scenario 3: Marcus is a new graduate working in a spa. When he sees that his next client is 82 years old, he feels nervous and considers asking the receptionist to reassign the session to someone else. He tells himself, “Older adults are too fragile. I don’t want the risk.” What do you think?

- Key Point: Age alone is not a contraindication. With proper intake and adaptations, older adults benefit greatly from massage. Prejudice against working with older clients undermines fairness and client dignity.

Scenario 4: Addison learns that her new client is transgender. She feels uncertain and uncomfortable, thinking, “I don’t know enough about this community. I’d rather not take this client.” She debates canceling the appointment. What do you think?

- Key Point: Lack of familiarity is not a valid reason to refuse service. Professional therapists must commit to providing respectful and inclusive care for all clients, regardless of their gender identity or expression.

Scenario 5: Owen owns a clinic that markets to corporate professionals. When a young client covered in tattoos and piercings comes in for a massage, Owen thinks the client doesn’t fit his business’s “brand.” He wonders if he should suggest another clinic. What do you think?

- Key Point: Tattoos and piercings are personal expressions and do not diminish a client’s right to care. Therapists should set aside their personal preferences and treat every client with the same level of professionalism.

Scenario 6: Elena has a client who is HIV-positive. The client assures her that he is under medical care and has no contraindications for massage. Still, Elena feels fearful about “catching something,” even while practicing standard precautions. She considers turning the client away. What do you think?

- Key Point: Standard precautions ensure massage is a safe practice. Fear of contagion, even when precautions are followed, is rooted in stigma rather than evidence. Refusing clients based on health status, unless the client is truly contraindicated, violates nondiscrimination principles and client dignity.

Activity 3: Sliding Lines

Duration: 30-60 minutes

Goal: Learners discuss obstacles to ethics including autopilot, filters, and triggered emotions as they might occur in real-world situations. They hold one-on-one conversations with different peers to solidify concept knowledge and think critically about their own responses and reactions.

Setup Instructions:

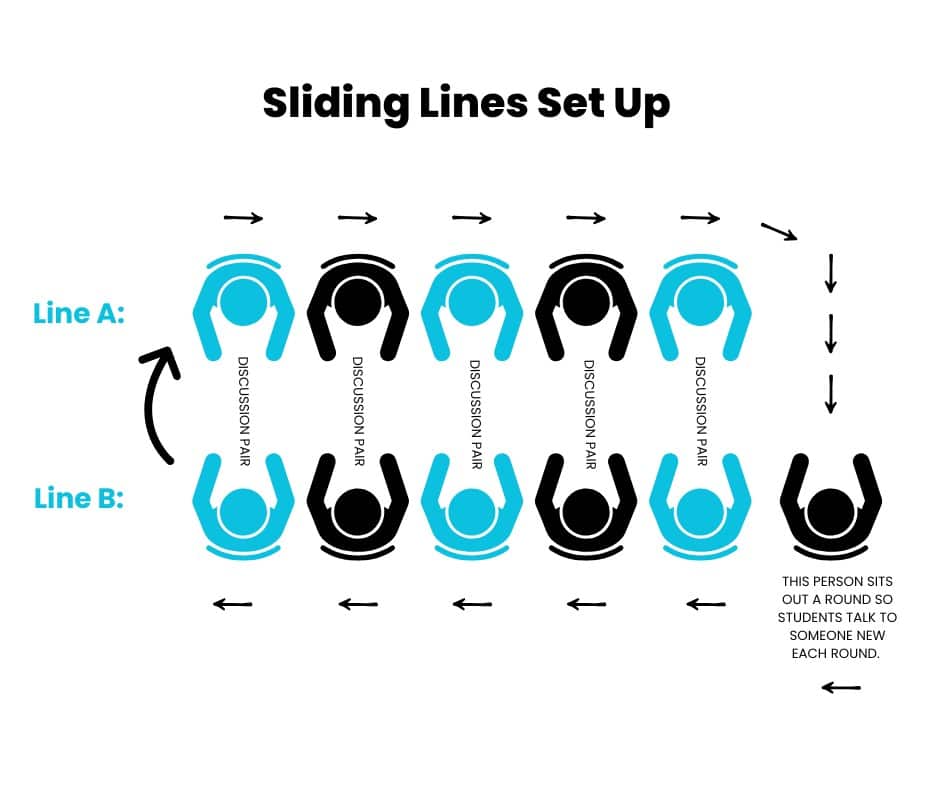

Physical Arrangement: Have learners place their chairs in two lines facing each other (see the diagram above). Their knees should almost touch, but they need enough room between the lines to stand up and move to the next chair on their right. The format works best with an odd number of students. You’ll place an extra chair in line B. As students arrive at this spot, they will sit out a round, ensuring that they hold discussions with several different classmates during the activity.

Activity Flow:

Step 1: Introduce a prompt. Set a timer for 1-2 minutes. Line A speaks first, sharing their information, thoughts, or ideas. When the buzzer sounds, set the timer again. Line B shares while Line A listens.

Step 2: Everyone slides one seat to the right. The student at the end of Line A moves to the extra chair at the start of Line B and sits out a round.

Step 3: Repeat. Continue this process until you work through all your prompts. Some prompts have two parts: Part One follows the timed format, and Part Two allows 2-3 minutes for open discussion between conversation partners.

Step 4: Wrap up Sliding Lines by moving into an anchoring activity (such as an active processing circle) to close this learning unit.

Sample Prompts

Prompt 1:

Imagine you’ve just arrived home from work. You drop your bag, check your phone, open the fridge, and start scrolling while snacking. Half an hour later, you realize you’ve eaten a full meal standing at the counter and can’t remember tasting any of it. You meant to go for a walk and call your friend.

Can you relate to this scenario about autopilot in daily life? Describe for your discussion partner how autopilot functions in your life in both positive and negative ways.

Prompt 2:

Part One: A therapist develops a plan for six sessions with a client seeking in-depth work to address specific postural patterns. In their early sessions, the therapist feels they’re making excellent progress. At the fourth session, the client admits that they haven’t practiced the assigned stretching exercises between sessions and requests a relaxation massage instead of clinical work.

Discussion Question: What thoughts, feelings, and emotions might the therapist experience hearing this news from the client?

Part Two: Before switching seats, ask students to discuss how they each responded to the scenario. Specifically, have them describe to each other how their filters influenced their responses. For example, if a student has a filter that “people should make a plan and stick to it,” they’re likely to respond differently than a student whose filter is, “The customer is always right.”

Prompt 3:

Part One: Person A is standing in line at a café when Person B abruptly cuts in front of them. Person A snaps, “Hey! There’s a line!” Person B apologizes, saying they didn’t see Person A. Everyone is looking at Person A, who feels embarrassed because they realize they overreacted.

Discussion Question: What’s going on in this scenario? How would you feel and act if you were Person A? How would you feel and act if you were Person B?

Part Two: Before switching seats, clarify that the scenario is about a triggered response. Ask students to compare and contrast their responses. Ask them to identify the filters, upbringings, or past experiences that influence how they predict they would respond as Person A and Person B.

Prompt 4:

Part One: A student is applying massage to an exchange partner. The instructor walks up and says, “I want to correct your application technique. Can I share some feedback with you?” The student says, “No! I’ve got it. I know what I’m doing! I’m only doing it wrong because you’re watching me and making me nervous.”

Discussion Question: What’s happening in this situation? What might the student therapist be thinking and feeling at this moment? What about the teacher? What might the teacher be thinking and feeling?

Part Two: Before switching seats, clarify that the scenario is about filters and triggered responses. The student may have a filter that suggests “I have to do things right or it means I’m not talented,” causing a defensive emotional response. Before we move on, take a moment to discuss your personal responses to receiving feedback. When someone wants to correct you, how do you think, feel, and react? What filters or previous experiences drive your behaviors?

Prompt 5

Part One: A therapist has worked with a client over several months to address chronic pain from a car accident that happened two years ago. As the therapist asks, “How was your pain after our last session? What should I know as we begin today?” the client bursts into tears, saying, “Massage isn’t working. Nothing is working!” The therapist feels their stomach constrict and their heart start to pound. They have an overwhelming urge to flee the session room.

Discussion Question: What’s happening in this situation? What might the therapist be thinking right now, and how would you feel if this happened to you?

Part Two: Before switching seats, clarify that the scenario involves a therapist having a triggered response that might be due to a filter, such as “I’m not a good enough therapist,” but it could also be due to other filters or subconscious experiences. Before we move on, take a moment to compare and contrast your reactions to the scenario, noting both the similarities and differences. What filters or experiences would drive your reactions if this happened to you?

Prompt 6

Part One: A therapist begins a session with a client they’ve treated weekly for several months. About twenty minutes into the session, the client says, “Can we stop? I’ve had a sinus infection for a few days, and the pressure from lying in this face cradle is making my head pound.”

Discussion Question: What’s happening in this scenario, and what step in session planning did the therapist miss?

Part Two: Before switching seats, clarify that the scenario involves a therapist slipping into autopilot and forgetting to inquire about any changes to the client’s health since the last session. Even with clients we see regularly, we need to check in to ensure there have been no changes to their health since their last visit.

Tips for Instructors

- Adjust your timing accordingly based on the complexity of the prompts and the level of conversation.

- Monitor energy levels and adjust the number of rotations as needed.

- Encourage active listening as well as sharing.

- Make sure to have a processing circle or time for students to journal at the end of this activity, allowing them to process their experiences.

Active Processing Circle After the Sliding Lines Activity (10-20 Minutes)

An active processing circle helps students consolidate their learning and experiences, grounding their energy before leaving class or moving on to something new. From the Sliding Lines activity, ask students to form a circle of chairs and take a seat. Pose a reflective question and ask students to share their insights in order, starting with a student who usually feels comfortable sharing and moving to the right. Pose between one and three questions and then conclude the circle by sharing your thoughts about the class. Thank students and end the class, or send students on a break. Possible reflective questions include:

- What did you learn about your own patterns of thought, feeling, or behavior during today’s class?

- Which discussion prompt challenged you to think differently about yourself?

- Did you recognize any personal filters, like particular beliefs or assumptions, that shape how you interpret other people’s actions?

- What’s one insight from today that you can carry into your massage practice or daily life?

- How might increased self-awareness improve your current relationships with friends, family, and classmates and your future therapeutic relationships with clients?

- What commitment can you make to yourself about managing autopilot, filters, or triggers in your professional role?

In Closing

These three activities represent just a small sample of what’s possible when you build ethics education around scenarios. Each one asks students to do more than passively absorb information. Scenarios require active engagement, critical thinking, and the kind of peer-to-peer discussion that deepens learning and builds professional judgment.

What I love most about scenario-based learning is that it meets students where they are. It doesn’t assume they already know how to navigate ethical dilemmas or that they’ve thought through their own biases and assumptions. Instead, it creates a safe space for exploration, mistakes, and growth. This is exactly what our students need as they prepare to become ethical, reflective practitioners.

If you’re looking for ways to make ethics education more engaging and impactful in your massage therapy classroom, I encourage you to give scenario-based activities a try. Your students will thank you for it, and so will their future clients.