Three Easy Guided Reflection Formats for Massage Educators

Introduction

Whether students have just practiced a new technique, discussed complex anatomy, explored contraindications, or worked through a case study, the moments after active learning offer some of the richest opportunities in your classroom. Guided reflection transforms these moments from casual debriefing into intentional learning experiences that deepen understanding, build clinical reasoning skills, and help students integrate new information into their existing knowledge.

Yet many instructors hesitate to incorporate structured reflection, worried it will feel awkward, take too much time, or require extensive training to facilitate. The good news? Effective guided reflection doesn’t need to be complicated. With just a few simple formats and clear facilitation steps, you can help your students extract more value from every learning experience, whether they’ve just received a lecture on the nervous system or spent an hour practicing myofascial techniques.

Kolb's Experiential Learning Cycle

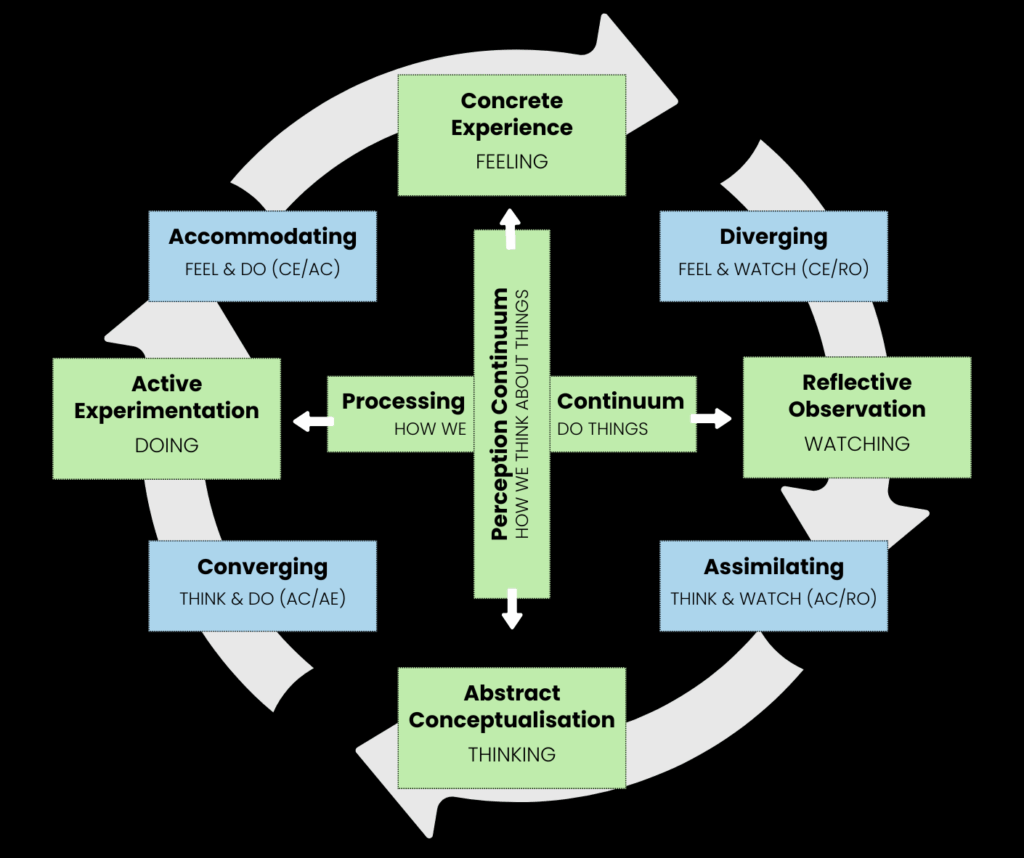

Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle helps explain why guided reflection is so critical for adult learners. Adults do not learn simply by having experiences; learning deepens when experience is intentionally examined, interpreted, and connected to meaning. In this model, reflection sits between concrete experience and abstract conceptualization, acting as the bridge that transforms doing into understanding. Guided reflection slows learners down long enough to notice what happened, explore sensory and emotional responses, and examine assumptions before moving into analysis or action. For adult learners, this reflective pause supports the integration of lived experience with prior knowledge, professional identity, and future application. Learning becomes intentional, transferable, and continuous rather than incidental.

Why Guided Reflection Works

Reflective practice entered mainstream adult education in the 1980s, when researcher Donald Schön published “The Reflective Practitioner,” introducing the concepts of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action for professional learners. Around the same time, David Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle positioned reflection as the critical bridge between experience and understanding. Reflection is the moment when students make sense of what they’ve just encountered and connect it to broader principles.

For massage therapists and bodyworkers, this matters tremendously. Our work integrates complex theoretical knowledge with embodied, experiential practice. Students need structured time to process what they’ve learned, felt, noticed, and experienced. Without this processing time, valuable insights slip away, theoretical concepts remain abstract rather than applicable, techniques stay mechanical rather than intuitive, and students struggle to adapt their learning to real clinical situations.

Research on reflective practice in health professions shows clear benefits including improved clinical reasoning, stronger self-awareness, better integration of theory and practice, and enhanced ability to learn from experience throughout one’s career. Try these three simple formats in your classroom tomorrow:

Format 1: What? So What? Now What?

This deceptively simple three-question framework, developed by Rolfe, Freshwater, and Jasper for nursing education, works beautifully for bodywork students at any level and for any type of learning, from hands-on technique practice to theoretical discussions about pathology.

How to facilitate:

What? (2-3 minutes): Ask students to describe what happened during the learning experience without judgment or analysis. After hands-on practice: “What did you notice? What did you observe? What did you feel?” If working in pairs, have both giver and receiver share their observations. After theoretical content: “What stood out to you? What key points did you hear? What examples or explanations landed for you?”

- So What? (3-4 minutes): Guide students to analyze and interpret their experience. “Why did that matter? What surprised you? How does this connect to what we discussed earlier? What does this tell you about this technique, about bodies in general, or about your future practice?”

- Now What? (2-3 minutes): Help students identify concrete next steps. After practice: “What will you do differently next time? What do you want to practice more?” After theory: “How will you use this information? What do you want to explore further? What questions do you still have?”

Why it works

This format prevents students from getting stuck in description (“it felt good” or “the lecture was interesting”) or jumping straight to judgment (“I did it wrong” or “I’ll never understand this”). The progression naturally builds clinical reasoning skills and helps students see connections between classroom learning and clinical application.

Format 2: Plus/Minus/Interesting (PMI)

Developed by Edward de Bono as a thinking tool, PMI asks students to examine an experience from three distinct angles, which is particularly valuable after trying a new technique or grappling with challenging theoretical content.

How to facilitate:

- Set up the categories (1 minute): Explain that students will reflect on three aspects: Plus (what worked well, what clicked, what they want to remember), Minus (what was challenging, what confused them, what they’d like clarified), and Interesting (what surprised them, what they’re curious about, what questions arose).

- Individual reflection (3-4 minutes): Give students time to jot down thoughts in each category. Emphasize that “Minus” isn’t about failure, but rather about identifying learning edges. For theoretical content, the Minus category often reveals misconceptions you can address.

- Pair or small group share (4-5 minutes): Have students share one item from each category with a partner or small group. Encourage them to notice patterns such as, are several people finding the same concept challenging? What common curiosities emerged?

- Harvest insights (2-3 minutes): Ask the full class: “What patterns did you notice? What surprised you about others’ experiences?” This helps students see that their challenges are often shared and that different people notice different things.

Why it works

The structured categories prevent students from fixating on what went wrong or what confused them. Even struggling students will find something in the Plus column, and strong students will identify learning edges in the Minus column. For instructors, the Minus category provides invaluable real-time feedback about what needs clarification.

Format 3: One-Minute Paper with Prompts

This quick written reflection, adapted from classroom assessment techniques, works exceptionally well at the end of a practice session, after a lecture, or at the close of a class day.

How to facilitate:

- Choose your prompt (keep it specific): Examples for hands-on practice:

- “What’s one thing you understand better now than you did an hour ago?”

- “Describe one moment when your hands gave you clear information about the tissue you were working with.”

- “If you could practice one thing for 15 more minutes right now, what would it be and why?”

Examples for theoretical content:

- “How does today’s content about [topic] change how you’ll approach [specific situation]?”

- “What’s one question you’re taking away from today’s discussion?”

- “Explain [key concept] in your own words as if you were teaching a friend.”

- “What’s one connection you made between today’s material and something you already knew?”

- Write in silence (2-3 minutes): Have students write without stopping. Emphasize that this is informal and grammar and complete sentences don’t matter. The goal is to capture thoughts before they evaporate.

- Optional share (3-5 minutes): Invite volunteers to share what they wrote, or have students share with one partner. Some instructors collect these papers to review later, which provides valuable insight into student learning.

- Close the loop (1 minute): Acknowledge common themes or questions that emerged. If several students share the same question, address it briefly or note that you’ll cover it in the next session.

Why it works

Writing creates a different kind of processing than speaking. It allows introverts time to think, creates a record students can review later, and helps instructors assess learning in real-time. For theoretical content, it reveals whether students can articulate concepts in their own words, which is a key indicator of genuine understanding.

Making It Work in Your Classroom

Start small. Choose one format and try it after one learning segment, whether that’s a hands-on practice session, a lecture on anatomy, or a discussion about professional ethics. Notice what emerges. You might be surprised by the depth of insight your students offer when given structure and time to reflect. As these formats become familiar, you can vary them based on your goals: use What/So What/Now What when you want to emphasize application, PMI when you’re introducing challenging new material, and One-Minute Papers when you want quick feedback or closure.

The key is consistency and genuine curiosity about what your students are experiencing and understanding. When students see that you value their reflections and use their insights to inform your teaching, they’ll engage more deeply with the process. Over time, they’ll internalize these reflective practices, becoming practitioners who naturally pause to learn from their experiences, which is exactly the kind of thoughtful, evolving therapists the profession needs.